The Power of Knowledge-Sharing

“KUA was called into being by one of our kupuna (elders), Uncle Mac Poepoe, who gave it life and breathed it into existence,” says early KUA co-founder Debbie Gowensmith. Debbie supports community-driven movements and played a key organizing role as KUA came to life, today serving as Vice-President of Groundswell Services.

On the Hawaiian islands, the loss of stewardship traditions and cultural practices that connect people with ʻāina (land or earth—literally “that which feeds”) has impacted every area of community life and health, including people’s ability to feed themselves.

“Models indicate that the current resident population in Hawaiʻi is not much larger than that of pre-Western colonization,” says Debbie, “and the people pre-colonization were feeding themselves just fine. Since then, the output of Hawaiian fisheries has declined 80-90 percent. The kuaʻāina—the grassroots community folks—are the experts in fisheries management.”

“Hawaiians are not stewards. They are kin,” says Aunty Makaʻala Kaʻaumoana, KUA board member and executive director of Hanalei Watershed Hui. “Living on a small island, the most remote landmass on planet earth, gives you a unique perspective on your responsibility. Fishermen know things scientists never will.”

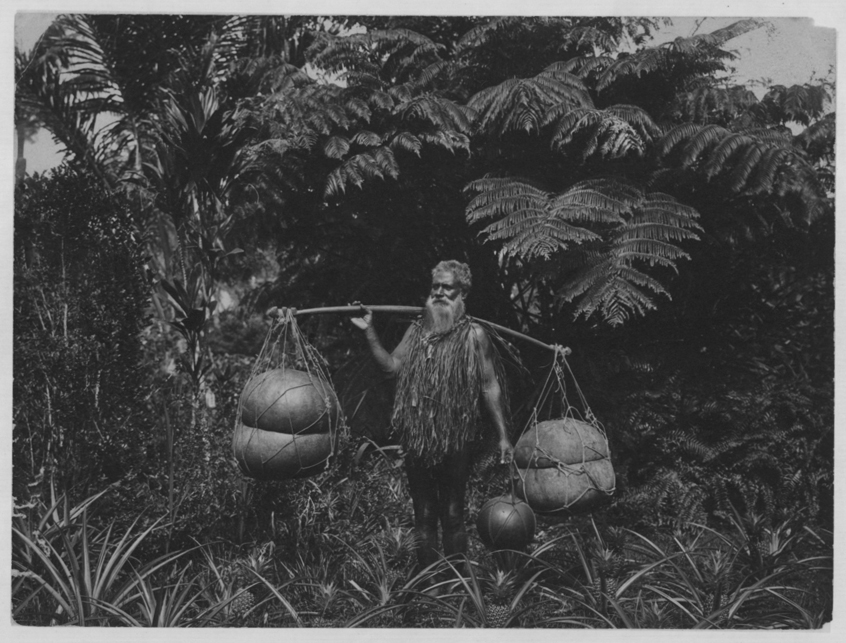

Kelson “Mac” Poepoe, a fisherman from Hui Mālama o Moʻomomi, Molokaʻi, experienced the worrying trends first-hand in the ocean, on land, and in his community

In the Beginning

Understanding that the community deserved more input into the management of water and land, Uncle Mac called for a gathering to share knowledge and reclaim traditional cultural practices and rights. The first meeting occurred in December 2003, a gathering of 13 communities in Moʻomomi with funds from longtime supporters the Harold K.L. Castle Foundation and the Hawaii Community Foundation.

That first meeting started a chain reaction. “Their very first priority was to transmit knowledge from elders to youth,” says Debbie. “Five weeks after the first gathering, one of our elders passed away, and it solidified that purpose.”

In 2004 a second gathering was held on Oʻahu, where young people made short films to capture kūpuna wisdom. By 2005, CCN was facilitating twice-annual gatherings. By 2006, the work began to deepen and spread. Appropriately, people learned of the network by word of mouth.

During those early years, the network facilitated the planning for Mālama Pūpūkea-Waimea, an organization on Oʻahu dedicated to education and protection of over 100 near-shore acres including a mile of coastline. The group instituted the successful Makai Watch. This partnership with the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) empowers citizens and NGOs to promote rules, report violations, educate, and monitor marine resources throughout the state.

As momentum continued to grow, the network supported a string of neighboring communities on Kauaʻi, including Hāʻena, Waipā and Hanalei. Caretakers visited one another and learned how others exercised their kuleana (rights and responsibilities) to care for the resources in their unique places.

Growing and Facing Challenges

In 2006, national fishing groups tried to insert right-to-fish bills into Hawaiʻi state policy. Suddenly communities in the network split on what they thought would be best for their place related to the potential regulatory changes. The group would emerge from this crisis stronger, as it helped them realize what was right for one place might not be suitable for another. They needed to trust each other’s place-based knowledge and wisdom.

By 2008, the network adopted the name E Alu Pū, suggested by member and fishpond caretaker Hiʻilei Kawelo. The phrase describes how the pualu (a type of surgeonfish) swim together in schools; it’s a command or call: move forward together. The network communities continued to let Debbie know that they needed technical assistance, organizing, and policy support she and others were providing.

With the network’s commitment and under Debbie’s leadership, CCN became the Hawaiʻi Community Stewardship Network (HCSN) the following year. HCSN continued to support the E Alu Pū network. By 2012, they decided to form a non-profit organization and adopted the name Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo (KUA).

The definition of the Native Hawaiian term kua is “back” like a “backbone” that holds up and fortifies the greater body. Kuaʻāina represents the grassroots, rural peoples of Hawaiʻi. Ulu means “to grow”, and ‘Auamo is a carrying stick held on multiple shoulders to share the burden of carrying something of great weight forward. Together the phrase means “grassroots growing through shared responsibility.” Miwa Tamanaha and Kevin Chang became KUA’s co-directors, incorporating the organization and beginning the continual work of fine-tuning its structure for maximum effectiveness. Around that time, the E Alu Pū network also formed a youth council for leadership development, mentoring, and succession.

“I keep seeing all the challenges we have,” says longtime member Uncle Damien Kenison, a fisherman in one of the last remaining traditional Hawaiian fishing villages, in Hoʻokena, Hawaiʻi. “It’s more than trying to retain our fishing rights. It’s trying to affect the political process. We need to have a good understanding of what our community needs, each of us, and then KUA’s role is to help us achieve that goal.”

The logistics of bringing people together from different islands can be challenging. “It’s tough getting a bunch of kūpuna like me to the airport,” says Aunty Makaʻala. “Maybe they don’t have a credit card or don’t want to sleep on the ground anymore. Over the years, Debbie figured that out, bringing people together and making everyone happy. KUA is still very good at that.”

During those early years, the network helped support the Hui Makaʻāinana o Makana in the development of a management plan for a community-based subsistence fishing area in Hāʻena, Kauaʻi. This effort took over 15 years of community organizing and more than 40 community meetings and habitat assessments that included traditional ecological knowledge gathering. The state eventually approved the plan in 2013, and the Hāʻena CBSFA became the first officially designated subsistence fishing area in the state in 2015.

“The state created a law based on the work of Uncle Mac. It’s the only law I know of in the state that allows the community to partner in co-governing resources, and it’s driven specifically by native Hawaiian voices of place,” says Kevin.

Connecting Past, Present and Future

The impact of KUA’s work to connect community around traditional ecological knowledge continues to grow. Today, the E Alu Pū network has grown to over 40 community-based stewardship initiatives, families, and organizations that are working to mālama (care for) dryland forests, taro farms, fishponds and fisheries across Hawaiʻi. KUA also supports and facilitates a statewide network of traditional Hawaiian fishpond projects and practitioners called Hui Mālama Loko Iʻa as well as a growing network of limu (native seaweed) practitioners, educators, researchers, and community stewards known as the Limu Hui.

The work is bigger than any one organization. It is a movement.

“What is an origin story? Everything begins before it begins,” says Miwa. “We can go back into the Hawaiian renaissance and joy and music being an inception point and then bringing back language. Today there are more speakers of Hawaiian than ever. There’s innovation all around us to continue to create those spaces to share knowledge.”

Going back further, E Alu Pū youth council member and taro farmer Josiah Deluze describes the effective land and sea management practiced in Hawaiʻi before Western contact.

“From a Hawaiian perspective, we have a good model of as near as you can get to a perfect community,” he says. “Each land division from mountain to sea has a caretaker. Each is a community, and everyone has a role: from the upland farmer to the nearshore fisher. Then you come together and share what you have with a super complex trade system. Everyone knows their role, and they share and help each other build.”

“It’s called the konohiki mindset,” says Kevin. “Their work was to connect the people and the place to the government.” In the Hawaiian Kingdom era, the konohiki was often a kaukau aliʻi (lower chief) who managed resources with the people of an area. In later times, the term became synonymous with land manager.

“The word konohiki means to invite ability [and] willingness. This refers to the ability of a konohiki to organize people for collective endeavors no one family could achieve alone…” (Carlos Andrade – Hāʻena: Through the Eyes of the Ancestors, 2008)

“The way that Western management breaks things up—out waters, near waters—it’s so screwed up,” says Debbie. “In terms of the future, I would love to see a system that enables more effective management based on traditional Hawaiian principles and knowledge.”

One of the network’s efforts in shifting this paradigm includes advocating for Native Hawaiians and community practitioners to have more of an active role in decision and policy-making processes and to fill positions as researchers, community planners, and within government and funding agencies. An example of this is the current Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) position held by Edward Luna Kekoa. Luna was one of KUA’s first employees and the network helped establish the role within DLNR.

In an increasingly connected world, the work also extends beyond the islands. In 2016, the E Alu Pū Global Gathering brought together people from more than 30 countries ahead of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) World Conservation Congress. By sharing knowledge, participants could continue to accelerate their efforts by recognizing common struggles and making connections across geography and culture.

“KUA has always existed,” says Aunty Makaʻala. “During Makahiki, when Pleiades rises in the sky and no wars are allowed, we would gather in ancient times. All native people get that. We’re coming back to our roots in our contemporary times with political acumen thrown in.”

The movement continues to grow, empowering communities across Hawaiʻi to work together toward a shared vision of ‘āina momona—abundant, productive ecological systems that support community well-being. In 2019, the KUA networks brought together hundreds of grassroots people from 80 different organizations. That same year the United Nations recognized the communities of Moʻomomi and Hāʻena for decades of work to steward their places by awarding them with the Equator Prize. During the Covid-19 pandemic, KUA continues to gather communities virtually, leveraging resources, partnerships, and the wisdom and solutions of the kuaʻāina people to address some of Hawaiʻi’s most difficult social and environmental problems and to build a better, more just and resilient future for generations to come.

“There is no last chapter for KUA,” says Aunty Makaʻala. “It will evolve and progress as long as it’s addressing real issues with the truth.”